The Familiar Face of Fear

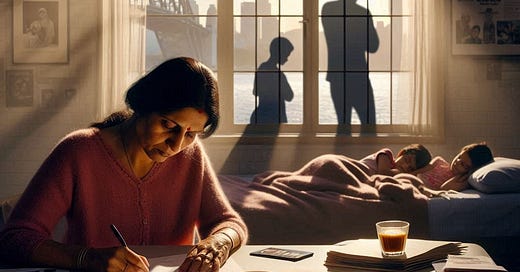

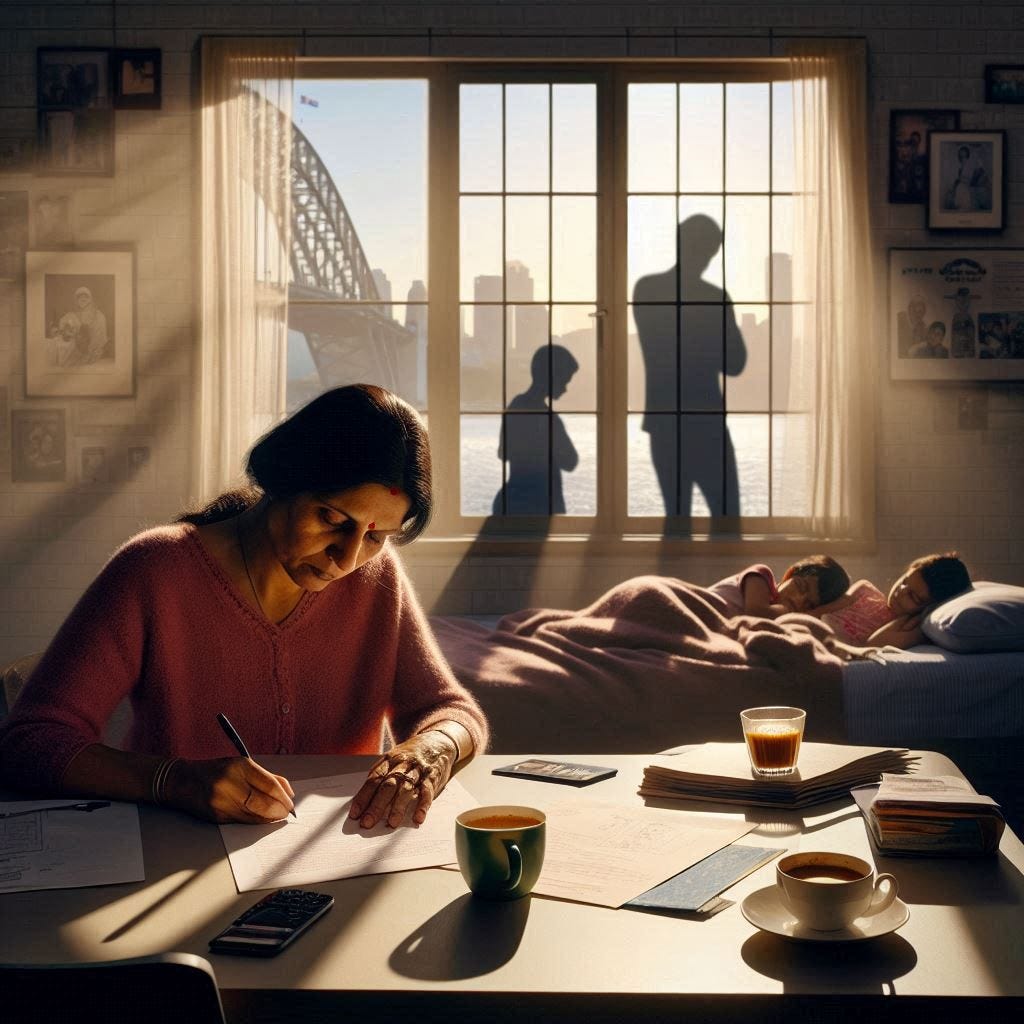

A short story - A woman builds a new life on another continent, but some fears can't be left behind.

Dear Vikrant,

Last night, I heard your footsteps again. Three years in Australia, and still, the sound of someone walking heavily down the hallway sends ice through my veins. Aditi woke up screaming, and for one terrible moment, I thought she had seen you too. But it was just a nightmare—the ordinary kind, not the kind that once lived in our home in Chandigarh.

Do you remember the night you held the kitchen knife to Rohan's throat? He was only four. You said it so calmly, as if you were discussing the weather: "I could end him right now, Pavita. And then Aditi. And then little Arjun. And save you for last, so you can watch." All because I had asked if I could visit my parents for Diwali. Our son still has a tiny scar where the blade pressed too hard. He tells his Australian friends it was from a cooking accident. Another lie to protect your memory.

The irony isn't lost on me—how I'm now the one keeping your ghost alive when I worked so hard to escape you alive.

Sydney is beautiful in ways you would have hated. Too free. Too vibrant. The children are blooming here in the salt air and sunshine. Rohan is twelve now and plays cricket with a passion that reminds me of you before—before whatever darkness took hold of you became your entirety. He has your talent but none of your rage. I watch him carefully for signs, but so far, all I see is a compassionate boy who walks elderly neighbors' dogs on weekends.

Aditi is learning piano. Remember how you smashed her toy keyboard when she was five, saying the noise gave you headaches? Now she practices for hours, and sometimes I sit outside her door just to listen, marveling at how something so beautiful can come from a child who witnessed so much ugliness.

And Arjun—he barely remembers you. Sometimes that feels like my greatest victory. He was only two when I put those sleeping pills in your tea, when I watched you drift off on the sofa, when I finally gathered enough courage to do what the police, my parents, your parents, and three restraining orders couldn't accomplish. He doesn't remember the weight I dragged to the car that night, or the drive to the Sukhna lake. He doesn't remember how many rocks I tied to you before pushing you over the edge, or how I vomited afterward, sinking to my knees in the dirt, both horrified and relieved.

Sometimes I wonder if anyone ever found you. Probably not. No one visits that side of the lake. It’s deep in the woods. You showed it to me. You said you will dump our bodies here and no one will ever find them. I learned so much from you.

The Australian authorities were surprisingly easy to convince. A widow with three children seeking a fresh start. My parents sold their home to pay for our relocation. My father pulled strings with old university connections. A family with a tragic but simple backstory: a missing husband, a political refugee. Not a monster. Suspected murder victim. Just another of politically motivated disappearance. Another one where people acknowledge with appropriate sympathy before moving on.

But you know all this, don't you? Because somehow, despite the sleeping pills, despite the rocks, despite the well, despite the 10,000 kilometers between Chandigarh and Sydney, you're still here.

Last week, I saw a man with your build at Arjun's school. Same height, same shoulders. He was just another father picking up his child, but I nearly collapsed on the spot. I sat in my car for an hour afterward, unable to drive, unable to breathe. The school counselor called me in the next day, concerned because Arjun had mentioned "Mummy had one of her scared times again."

They think it's PTSD. A convenient diagnosis that explains away my jumpiness, my nightmares, my occasional dissociation. They're not entirely wrong. But what they don't understand—what I can never tell them—is that my fear isn't just of what happened. It's fear of what I did. And fear that somehow, impossibly, you survived.

They tell me I shouldn't write to you. My therapist says these letters only keep you alive, that I'm anchoring you to this world when I should be letting go. But how do I explain that you were never the type of man who needed permission to exist? That whether I write or not, you visit me anyway?

Rationally, I know you're dead. No one could have survived what I did to you. But rationality has never been our strong suit, has it? You weren't rational when you threatened to set me on fire while I slept. I wasn't rational when I stayed after the first time you put me in the hospital. And now, the most irrational thought of all haunts me: what if the man who defied every expectation in life has somehow defied death too?

The neighbours here think I'm charming. "Such a devoted mother," they say. "So brave, raising three children alone." If they only knew what devotion really meant in my case—that I ended a life to save three others. That I carry the weight of not just trauma but murder. That every time I check the locks at night (three times, always three), I'm not just keeping danger out, but keeping my secret in.

Sometimes, in my darkest moments, I think death would have been easier than this constant vigilance. But then Aditi brings home an art project, or Rohan tells a joke at dinner, or Arjun falls asleep against my shoulder, and I remember why I had to become something I never thought I could be.

I've started volunteering at a women's shelter. I can spot the ones like me instantly—the ones still living with ghosts. I never tell them my story, but I sit with them in silence, and sometimes that's enough. The director says I have a gift for calming the most frightened women. If only she knew that it's not a gift but a kinship—we are all murderers in our minds, even if most never cross the line I did.

Yesterday, Rohan asked if we could visit India someday. "I barely remember it," he said. "And Arjun doesn't remember it at all." I changed the subject, but the question lingers. How do I tell them that we can never go back? That somewhere in that country, in a dried-up well surrounded by superstition, lie the remains of their father? That crossing those borders might somehow give you power again?

The children speak with Australian accents now. They eat Vegemite and say "no worries" and complain about the December heat at Christmas. They are becoming people you never knew, and I'm grateful for that distance. But I am still the woman you knew—the one who trembled when you raised your voice, who learned to sleep with one eye open, who ultimately chose survival over morality.

Sometimes I dream that you climb out of that lake, dripping with fetid water, rocks still tied to your limbs, and begin the long walk to Australia. In these dreams, you never run. You never need to. You just walk steadily, inexorably, crossing oceans as if they were puddles, and I know that no matter how far I go, you will eventually arrive at my door.

But then I wake up. The Sydney sun streams through my window. I hear the children moving about the house. And for a moment—just a moment—before I remember everything, I am simply a woman beginning another day.

Until tomorrow's letter,

The wife who loved you, feared you, killed you, and somehow, still cannot escape you,

Pavita

If you liked this story, please restack it so that others can read it too.

Regards

What a haunting story. It felt so real I expected the end to say he’d shown up after all.

This is an awful story, as well as an excellent story

It seemed so true, as though it was the telling of what really happened.